A fan walks past Covid information signs outside Amex Stadium before the Brighton v Southampton game. Brighton, December 2020

Life in the Cocoon: Football during the Covid-19 Pandemic

In June 2020, the Premier League’s Project Restart resumed professional football in England for the first time since its suspension on 13 March, with stadiums empty of fans and extensive protocols in place to protect the game from the threat of Covid-19. At first, football behind closed doors seemed like a quirky interruption. We had all been so glad to have the sport back, in any form, that it was almost amusing to see crossbars sprayed with disinfectant and away teams emerge from unusual corners of stadiums, perhaps having changed in a version of the groundsman’s hut. The motivational tarpaulins which masked empty seats were colourful, and the summer weather did lend an air of cheery optimism to what was undoubtedly also a strange and unnerving return to the game.

The majority of the images in this essay, however, were taken over winter 2020, as the colder weather set in and the novelty of the situation wore off. The strange new rituals quickly became mundane; filling out health clearance forms and temperature checks were soon as central to my routine as packing my camera bags. I felt the absence of spectators more than ever during those months. In the dark, with the floodlights on, the pitches and their surrounding communities took on a sort of milky glow – a beautiful light for photographs, but a painful reminder to fans that matches were being played without them, just out of reach. Football grounds are primarily places for socialising, for seeing friends and escaping reality for a few precious hours. It is not for nothing that fans refer to their grounds as ‘home.’ The pandemic reinforced how important fans are to the game: they are the foundation on which their clubs are built.

Norwich City and Southampton players hold a minute’s silence for Covid victims. Norwich, June 2020

Manchester City fans zoom in to watch their team play Liverpool. Manchester, July 2020

Liverpool lift the Premier League trophy in the empty Kop stand. Liverpool, July 2020

The Away Concourse at Villa Park before Aston Villa v Leeds. Birmingham, October 2020

I often walked the empty concourses behind the stands just before a match started. These places would ordinarily have been vibrant and buzzing with anticipation, but without the crowds and the laughter they felt almost haunted. It was hard to miss the poignant reminders of those last ‘normal’ games: bookies odds for first goal scorer still scrawled up on whiteboards, adverts promoting events – some now notorious – in March 2020.

I found the sound – or the lack of it – the most surreal. Instead of the usual roar of fans, the only noise of a goal was the rippling of the net. Without an audience to perform to, celebratory routines were subdued, and games often concluded with a tame high-five or a polite handshake. The further you went up the football food chain, the larger the stadiums and the more unnerving it got. An empty Wembley Stadium was the ultimate echo chamber: the thwack of boot on ball would reverberate up and around the bowl before slowly fading away. When Manchester City and Everton players lined up before the Women’s FA Cup final to hear an immaculately dressed singer belt out Abide with Me, the anthem performed at just about every Cup final since 1927, the absence of thousands of voices in the stands felt almost crushing.

Abide With Me is sung at the Manchester City v Everton Women’s FA Cup final at Wembley. London, November 2020

Canvey Island supporters watch their team play their biggest ever game, an FA Cup second-round match against Borehamwood, from ladders overlooking the away end. Essex, November 2020

Brentford v Wycombe Wanderers, the first competitive match to be played at the new Brentford Community Stadium. London, September 2020

Perhaps the fans I felt most sorry for were those of Brentford and AFC Wimbledon. Both clubs made their long-awaited moves into new stadiums that year, with their supporters unable to enjoy the expected spectacle and celebrations. I attended the first competitive match at Brentford in early September. The perfect grass, cutting-edge architecture and empty, multicoloured seats gave the odd impression of watching a video game. Not until December were a few Brentford fans given the chance to visit their new home. The ‘grand’ opening of Wimbledon’s new ground at Plough Lane was even more eerie: the only presence of the fans who resurrected the club in 2002 were their own cardboard cutouts.

Cardboard cutouts of AFC Wimbledon fans at the first match, against Doncaster, at their new stadium. London, November 2020

Tottenham Hotspurs v Leicester, viewed from the huge empty South stand of the Spurs stadium. London, December 2020

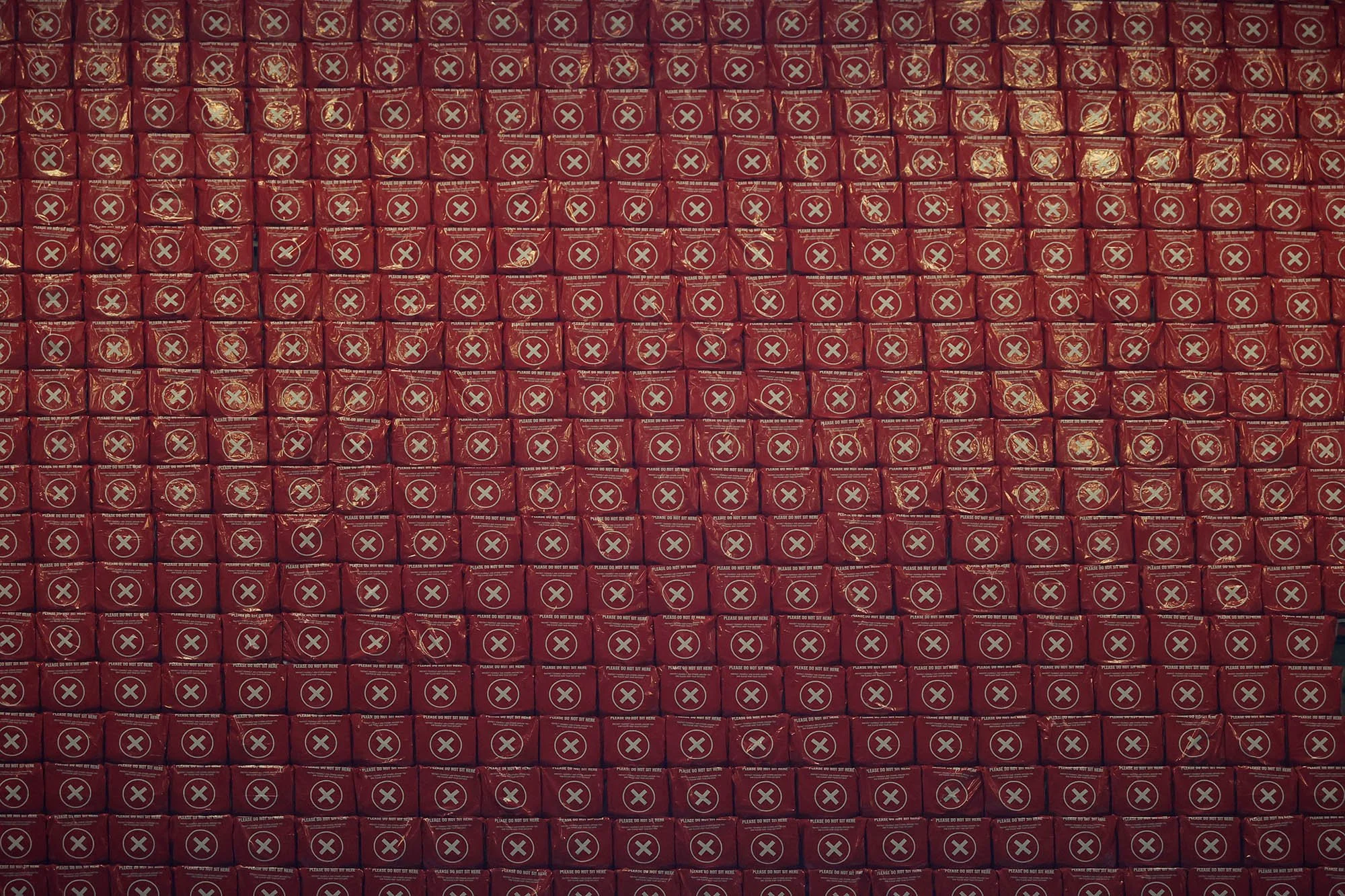

Empty seats marked with crosses at the Emirates Stadium. London, December 2020

The corner flag is disinfected before kick-off at Crystal Palace v Newcastle. London, November 2020

Joao Cancelo takes on Scott McTominay in front of the empty Sir Alex Ferguson stand during the Manchester United v Manchester City game at Old Trafford. Manchester, December 2020

At the beginning of December, the lockdown was lifted, allowing clubs in Tier 2 areas to host 2,000 spectators. These fans were introduced to a whole new world of football, one of arrows, one-way systems, and constant reminders. At West Ham, the huge screen on the side of the London Stadium scrolled through slides welcoming their supporters home, before urging ‘hands, face, space.’ For those in Tier 3, football still took place behind closed doors. The 80th Manchester Derby, played at Old Trafford, was an uncharacteristically dull game. Without the enthusiasm of the crowds, the players failed to bring their usual passion to the game.

The London Stadium before West Ham v Manchester United. London, December 2020